Thinking can prevent you from both saying and doing many things. Thinking is not saying or is it doing/acting. Thinking is always and ever a virtual action until the act of saying or an actual action is affected. Doing, saying and thinking are participles and they modify nouns: "What is John doing?" They are a type of verb, which functions to express actions and are similar to adjectives as they also modify actions. A person can engage in the action of saying something or doing something but wouldn't it seem somewhat odd to say that they were engaged in the action of thinking? Not entirely and I am not attempting to claim that thinking and acting are mutually exclusive behaviors. People just usually make an overall distinction between thinking and behaving, and that they are never the same thing. But I would like to distinguish and clarify some basic human functions: behavior (acting), saying (language) and thinking (cognition), so it may benefit the process if one was to distance and distinguish the terms. Ultimately it is probably the case that all of the terms are synonymous and are only differentiated for pragmatic, utilitarian, and everyday reasons--"I am thinking right now about the action I would like to take." Further it is quite possible that some instances of mental health disfunction are based on how an individual's extreme differentiation of these processes (thinking/saying/behaving) lead them to focus too much on any one of the three to the detriment of the others and themselves. For example: Someone may engage in the behaviors of working, blogging and dating. Any behaviors/actions can be inserted into this chain. All of these are examples of someone doing something. The question regarding mental health would be then to what degree (quality/quantity) does this individual achieve the outcomes they desire regarding each behavior that they have consciously chosen to engage? Ultimately, what barriers do they place before themselves (normally unconsciously) and conversely, what barriers do they encounter that are not self-imposed but that they are incapable of overcoming? Was it simply a goal too high and out of their range? Let us say that for this example the individual we are referencing is proficient in a descending ability: They are very good at their work life, they have moderate ability to blog and their dating life is abysmal. Why would it be that they are incapable of transferring their capabilities to function very effectively at work to boost their blogging ability and then completely transform their dysfunction at dating? The simple answer is that they are assessing the data points related to the other two tasks in a different manner than the task that they are proficient. Granted these "tasks" are highly divergent when viewed from the outside but once an individual begins to analyze the individual components in a objective, abstract and metaphorical way, that is through psychotherapy, then the associations and similarities begin to become quite evident. When the similarities are uncovered the potential for change is engaged because the unconscious barriers are discovered through comparison with the higher functioning behaviors, aka work in this example. There potentially are little to no barriers in some parts of your life. Let's identify those!, no matter how small it may initially seem, because it can be utilized to cast a bright, shining light on the other areas that are troubling and undiscovered.

1 Comment

Just as an automobile maneuvers a street so does your mind a thought, both start and stop, as the vehicle navigates a whole city so does your mind the relationships or dissimilarities between thoughts; both continue, starting and stopping until the final destination or conclusion is arrived at. The most obvious difference is the mind’s distinct ability to differentiate the external environment, a street or city for this instance, from the internal thoughts, the mind’s own internal environment, about the city or any other object it is thinking about. Troubles arise when the automobile’s driver does not see the green light turn to yellow and then, worse, red. This is so obviously devastating in the real world when an accident occurs; similarly with the mind, but usually with much less obviousness. The street an automobile travels is often illuminated by some source of light, be it a celestial object (sun, moon, stars), street lights or the head lights of the vehicle itself, the mind can have very dark corners a driver is often unable to or ill-equipped to navigate and satisfactorily maneuver. This is when a person may have an unfortunate instance of having a mental or psychological accident. The human brain could be thought of as the car in the above metaphor and as it houses the mind, the driver could be thought of as the mind. This car is the most complex object in the known universe. How well is it’s driver acquainted with its mechanisms, operation and required maintenance? This being known, how much more difficult is it for any individual to adequately navigate the roads/events of their lives without having breakdowns or accidents due to its inherent complexity? Not only is the car complex but the roads taken during the maturational process can be highly treacherous and danger filled. The young driver is incapable and ill prepared to handle the obstacles and pitfalls. The barriers and problems that are encountered are more often than not inappropriately navigated and the aftereffects that are not appropriately processed or “repaired” leave the vehicle in a state of disrepair. The driver is no longer able to freely and readily travel the roads that inevitably continue to present themselves. Therapy is a way for the driver to reacquaint themselves to their complex vehicle and then to better be able to reorient themselves to the roads that they not only must travel, but, then will enjoy, once again, travelling. The thought within your mind is a road travelled by your mind. The two are as intimately bound as is the car with the road it travels. Unlike the physical road and the car your mind can take “flight” and travel down roads that are so far up in the sky that there has not been yet a physical vehicle manufactured that could reach such similar heights. This can obviously be very good, as when you find a very creative impulse or devastatingly dangerous, as when that creative impulse leads you into a dark space of loss, despair and depression. Distinguishing how to moderate and thereby appropriately navigate how you create your mind-space or mind-set can assist a person in traveling safely. How does one travel safely? Well, as with a car that has a gas pedal and entropy producing brakes, so does your mind need countervailing mechanisms that produce thrust or momentum and then reduce or eliminate that movement forward or backward when it is necessary and appropriate. It is relatively simple to manipulate a gas pedal and brake after a few hours of instructed application. The same is not always true for instruction and implementation of the parallel mechanisms of the mind. The way the car has been managed are ultimately the most important factors for producing, re-engaging or reacquainting the driver to their throttle and brake: how well has the car been properly maintained and more importantly how roughly has the car been handled, by its owner and by those entrusted with its safety, i.e. its caregivers? These factors will play heavily into how easily an individual will be able to begin to right the direction their car has been traveling and a therapist can act as a driver’s instructor. By Mathew Quaschnick “How does therapy move forward?” and “why doesn't it seem to sometimes?” Nearly everyone who begins therapy will come up against both of these questions. Both questions are potentially very complicated to answer. Therefore, it will be the place of this article to only touch upon a basic way of illustrating some of the more general components of the processes involved. Then some of the complications people may confront will be introduced. As long as we keep it basic I believe that you will be able overlay or insert your personal experiences and then maybe recognize and prevent the stoppages and encourage the forward progressions.

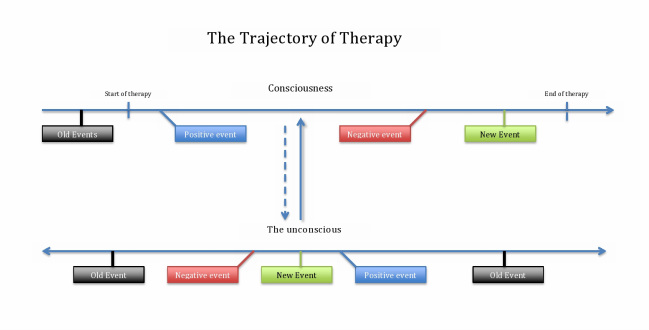

The accompanying graph has two horizontal lines, which are labeled “Consciousness” and “The unconscious.” These can be thought of as the individual’s ability to be aware, i.e. conscious, and the reality that sometimes we are not so aware of some things, i.e. the unconscious. An example of how we are not aware or are unconscious of something is simply your name. Your name remains unconscious until someone calls you by it or you see it written or as you are possibly thinking about it just now. So, back to the graph: The top line labeled “Consciousness” can be thought of as the materially physical and the temporal, time-dependent aspect. It is the part that you experience in you daily life and the part that your immediate awareness recognizes. The past, present and future are all on this line and you recall it based on its chronological order. The “Start of Therapy” could easily be the “start of the day” or the “start of the workday,” it represents the first session of therapy. Therapy continues down this line with positive, negative or “new” events. Therapy, however, does not move forward as easily and obviously as would your workday or any other day of your life. Therapy is, or at least should be, a very different experience from your normal daily life. The main reason why therapy is vastly different is the therapist should be looking for what comes out of your unconscious. This is unlike the interactions you will have with other people in your daily life. Normally people are just concerned with the “face-value” of what you are saying and how it effects them: “You want a Kit-Kat,” “Well I like Snickers.” The therapist is listening for your likes and dislikes, for sure, but they are not then comparing them to their own. The therapist is paying attention to your unconscious desire to talk about candy bars instead of the original reason you started therapy. Now back to “why does therapy seem to stop?” Positive and negative events occur all throughout therapy. One day therapy seems to click and you really feel like “I get this and I like it,” but then the next week there seems to be something off and for that matter you don’t even recall any of the positive events from the last week. A very simple way of illustrating this is the dynamic between the two lines on the graph. It is very easy to be happy or fulfilled by therapy on a good day where you experience what seems to be a positive movement forward; however, when that event is over, and for that matter even when a negative event is over, the idea of the event moves from your consciousness to the unconscious. Now the trick is that once it is in the unconscious there is no particular temporal placement for it and it is not easily recalled. The positive or negative events are both moved into the unconscious and are held there with all of the other events that have occurred in your lifetime waiting for a reason to be recalled consciously or being recalled unconsciously or unexpectedly because there was an associated event, similar to when your name is called out to you. The unconscious does not “discriminate” what goes in or what comes out and does not therefore “stop” therapy. What will stop therapy is the lack of communication between the therapist and yourself. The unconscious is always communicating to your consciousness. It is not always communicating in the language that you recognize. Why were you taking about candy bars again? It is the place of the therapist, their skill and experience, to build the relationship and rapport between them self and yourself, that is the communication between you and the therapist is model for the communication between you and your unconscious. This constant communication between yourself and the therapist mimics your unconscious and consciousness communication and will keep the therapy moving forward. By Mathew Quaschnick Transference is a psychoanalytic term originating in the early work of Sigmund Freud. The term has been utilized to refer to the same "experience" in therapy but, depending upon the theorist discussing the concept, it is always described in many different ways. This makes the term very unique, very powerful but also very difficult and sometimes useless.

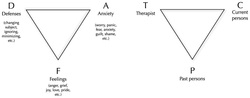

The experience of transference occurs on the side of the the person engaged in therapy, that is it originates in the client's psyche. It is a psychological process that moves from the psyche of the client, via projection, onto the therapist. "Countertransference" is the term utilized when the therapist has the experience themselves. Just as the client is normally unconscious of the projection, so will the therapist not normally recognize or be conscious of the projection he imposes onto the client. The therapist may have the skill to prevent themselves from projecting and awareness to notice that they are projecting depending upon their level of skill and self-awareness. The fact that there is a projection is what distinguishes transference, regardless of whether it originates in the therapist or client. However, to maintain a sense of simplicity and to entertain the idea in a basic way transference always begins in the client and moves toward, or is projected at the therapist. The essential qualifying factor for transference is that an emotion is engaged by and then elicited, projected by the client at the therapist and that the client then believes, consciously or unconsciously (more on the importance of it not needing to be conscious below), that the therapist behaved or acted in a way to warrant the emotion. The therapist, if conscious that he is eliciting the emotion can then investigate/analyze "why" the emotion was elicited, but if he is unconscious that it was elicited due to "transference" then the therapist is, at best without a direction to assist the client in healthfully processing the emotion--which is not good; and at worst, the therapist may become offended or lash out at the client--which is detrimental. The therapist should know that the he should -- NOT -- engage on a personal, or directly emotional level with the client otherwise the therapist risks the relationship and any potential positive therapeutic value that is inherent to the projected emotion. Jaques Lacan utilized what he called the "L schema" to assist would be therapists (Psychoanalysis calls a therapist a "psychotherapist" and a client and "analysand"). Without going into too great of detail the basic idea behind Lacan's schema is that the therapist should not engage with the client from a person-to-person, or ego based perspective. They should instead engage the client from the Symbolic Register (or Symbolic Level). They should attempt to remain in a virtual state of reflection and not submit to the emotions. What is the symbolic value of the emotion and NOT "why the hell did you [the client] call me a bastard!?!" If the therapist doesn't know to NOT respond on the level of ego, or the Imaginary Register, then the therapy will more then likely devolve into an argument; thereby, greatly negatively impacting the relationship and potentially blocking any further positive therapeutic outcome. Transference can come from either direction but how the trained representative reacts to the individual situation is the key to any positive therapeutic outcome. By Mathew Quaschnick  Intensive Short-term Dynamic Psychotherapy (ISDP) utilizes two maps, Triangle of Conflict and of Person, for assisting the therapeutic processing of client behavior. ISDP favors this schematic for directing the behavioral as well as interventional material within the immediate moment and moments of the session as they are produced in the here and now. The triangle of conflict represents the dynamic flow of the client's unconscious material. The triangle of person is meant to pictorially represent the basic reality that the therapist-client relationship. There are three main components each representing an active conscious or unconscious dynamic in any given relationship. The client draws from these relationships: e.g. the therapist "T," past persons "P," and current persons "C" to determine how they should interact with someone. The client may respond utilizing the "triangle of conflict" when the therapist attempts to interact with the client while utilizing behavioral patterns that the client has utilized in the past. For example: If the therapist requests information about the client's presenting concern, let's say, "general depression," and the client talks about how they have not been able to "get to work on time" then this could be a defensive, or "D" response. The D response is meant to block the feelings, or "F" response, associated with the actual depressive feelings. If the client was able to answer the question about their depressive feelings then there may have been a chance for processing the emotions. However, the D response by the client instead wards off anxiety, and is an "A" response, in the triangle. All of the points: D, A and F--are connected and each time that the therapist asks a question or implements an intervention there is a chance for one of the resulting points [D, A and F] to be utilized by the client. It is not as simple as always wanting to get an F response but more so of the therapist being actively aware of each response and then associating the triangle of conflict responses back to the Triangle of People so that the client and therapist can begin to understand the historical as well as current relationships that have and continue to contribute to the client's main presenting problem, aka general depression--but it could be any mental health concern. By Mathew Quaschnick

|

UPTOWN THERAPY MPLSEdited and composed by Mathew Quaschnick

Sort articles by clicking below on ARCHIVES or CATEGORIES.

MENTAL HEALTH THERAPY

LOCATION AND HOURS:

1406 West Lake St. #204 Minneapolis, MN 55408

Monday - Friday: 9-5 PM with limited evening appointments

Archives

March 2017

Categories

All

|

|

Uptown Therapy is wonderful. I have benefited greatly these past 8 months and am sure to continue. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed